It’s no Field of Dreams, this bumpy patch of sun-baked earth with faded chalk lines, no bleachers, not a blade of grass and a drooping line of wire separating the outfield from houses where scraggly canines lurk. Yet this is where the dream took hold.

It’s where Mexico’s own The Natural honed his skills, his delivery featuring the signature skyward tilt, as if seeking heavenly intervention for his offerings from the mound.

“El Zurdo learned to pitch here,” recalled Filiberto Velázquez. “It’s hard to believe, no?”

El Zurdo — “The Lefty” — would be Fernando Valenzuela, the youngest of 12 children from this desert hamlet in northwest Mexico who would corral a blend of ineffable talent and gritty determination to electrify Southern California and the baseball universe.

A man places a candle at the base of a statue honoring late former Dodgers pitcher Fernando Valenzuela outside the Pan-American stadium in Guadalajara, Mexico, on Oct. 23. Valenzuela died died Oct. 22 at the age of 63.

(Alfredo Moya / Associated Press)

His last days and word of his death Tuesday were big news in Mexico, where the media followed his condition daily and plaudits poured in from athletes, politicians and others. “I think all Mexicans are sad for the passing of Valenzuela,” President Claudia Sheinbaum said at her daily news conference, which ended with a video tribute to the hurler. “Our solidarity with his family and with all of Mexico.”

Though the stadium in Hermosillo, the Sonora state capital, has long been named after Fernando Valenzuela, here in Etchohuaquila — population maybe 500 — there is no public monument to the native son, now more than four decades after the heady summer of Fernandomania.

The other evening, a group of young people outside Etchohuaquila’s only shop seemed perplexed when asked if they had heard of the region’s most renowned citizen. Then one answered.

“Yes, I know who he was — he played baseball with my father,” said 19-year-old Iván Valenzuela (no relation). “They say he was a great man,” he added, before jumping onto his motorbike and tooling away.

But, for an older generation, Valenzuela remains a vivid presence, both an inspiration and a reminder of youth. Velázquez, a former mayor in the area, is 63, the same age as Valenzuela when he died. One can hear the wonder still evident in his voice when he recalls the improbable trajectory of the soft-spoken grade-school dropout who left this place behind and became a baseball icon.

“He was a giant, a legend,” said Velázquez. “We are so proud that he came from our pueblo.”

Many here see the current Dodgers-Yankees World Series matchup as a throwback to the teams’ last postseason showdown — the memorable 1981 duel, during peak Fernandomania, in which a gritty Valenzuela led the Dodgers back from a two-game deficit to take out New York.

It’s a welcome diversion in a place — “town” is too generous a word — that has reverted to hard times. Most streets remain unpaved. Years of drought have devastated agriculture and the cattle industry that once provided a living for Valenzuela’s late father, Avelino, a vaquero who toiled for area ranches, though he could barely afford livestock of his own.

Yet his sons always had time for baseball, and young Fernando never lacked a partner: He had six older brothers to play with.

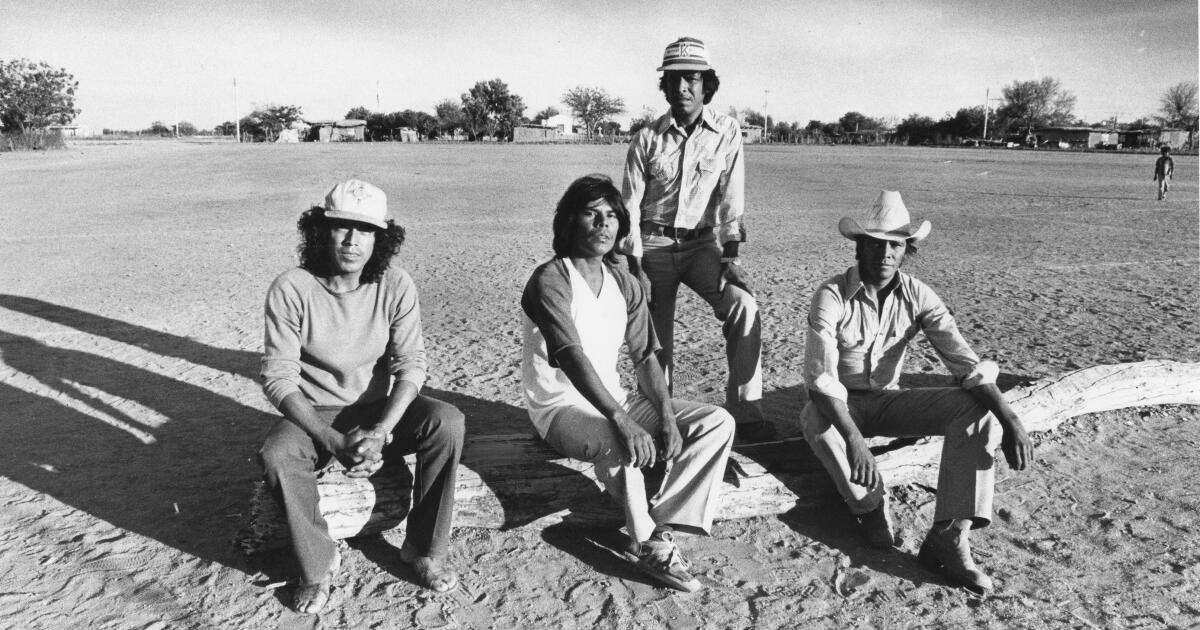

Father Avelino and mother Hermenegilda Anguamea de Valenzuela pose with eight of the 12 Valenzuela brothers and sisters in front of their family adobe in Etchohuaquila, in the municipality of Navojoa in the state of Sonora, Mexico, on April 27, 1981.

(Jose Galvez/Jose Galvez / Los Angeles Times)

“The Valenzuelas were a baseball family. I had the great privilege of knowing them well and being in their home many times,” said Casimiro Luna Serna, 76, former president of a regional amateur baseball league. “Fernando was raised between the bats and the balls. ”

Early on, he displayed uncanny skill.

“Even as a kid in school, he flashed that talent,” said Luna, who now runs a family carnitas restaurant along the main highway. “He had a different level of talent. He was a phenomenon from a young age. But he was always a very reserved person, he didn’t talk much — like everyone in his family.”

Eladio Castelo Gómez, now 73, recalls being on a local all-star team with Valenzuela when the phenom, then skinny and shaggy-haired, was only 16 or 17.

“I was a lot older than he, but I was so impressed,” said Castelo, who spoke outside his home after his daily horse-back jaunt through the desert. “He was just a boy, but there was that innate ability. He put down 17 batters in a row. And we became friends.”

During Valenzuela’s 1980s heyday, this entire area experienced its own version of Fernandomanía.

“When Fernando became famous, everything here changed,” said Luna, sitting at a plastic table at his family’s outdoor eatery. “When he pitched, everyone was watching on the television, or listening on the radio. People came from all over to see where Fernando was born. He made a lot of people love baseball.”

Valenzuela signed his first professional contract in 1978 with Los Mayos, a Mexican Pacific League team in the nearby city of Navojoa. The club is named after an area Indigenous group to which many area families, including the Valenzuelas, trace their origins.

“At that time we gave him a bonus of 5,000 pesos and a monthly salary of 3,500 pesos,” recalled Fernando Esquer Peñuñuri, former president of the Navojoa team. “That was a good salary,” said Esquer, now 85, seated in his home office, a Dodgers cap on his head and a Dodgers mug and Valenzuela bobble-head on his desk.

In today’s dollars, that’s a $1,034 bonus and a monthly paycheck of $724.

Fernando Esquer Peñuñuri, former president of Los Mayos, a team Fernando Valenzuela played for, recalls Valenzuela’s career.

(Patrick J. McDonnell / Los Angeles Times)

On the wall in Esquer’s office is a framed copy of the contract, with Valenzuela’s signature. A bookshelf displays baseballs bearing the signatures of baseball luminaries, including Valenzuela and Rickey Henderson — the future Hall of Famer who, before his major league debut, led Los Mayos to their first championship in 1978-79.

Valenzuela went on to various stops across the Mexican leagues before being noticed by legendary Dodger scout Mike Brito, who helped persuade the team to sign him. Valenzuela learned his iconic screwball — a pitch that few can master — not in Mexico, but in the Dodger’s’ minor-league system.

Youths here and elsewhere in Sonora state still play béisbol —the preferred sport across much of northern Mexico instead of soccer. And, while Mexican-born players continue to ascend to the major leagues, none has approached Valenzuela’s level of achievement or fame.

Today, the fans who once made the pilgrimage to Etchohuaquila from as far away as Southern California to view the birthplace of their idol are long gone.

Beyond the memories, the only trace of the great man is La Casa — the rambling, Spanish-style home with a terracotta roof, stucco walls and inlaid ceramic tiles that Valenzuela built for his family during the exhilarating, and financially remunerative, days of Fernandomania. The pitcher hired a well-known architect to design the one-story structure, which sits atop an elevated stone foundation on the same property where Valenzuela and his siblings were reared in a cramped home without running water.

Some here express disappointment that Valenzuela didn’t invest more in the community. Most area baseball diamonds remain derelict. Once his parents passed away, the star’s visits home became less frequent.

“Fernando wasn’t very dedicated to the people of his barrio — beyond his own family,” said Luna, the former league president. “He seemed to distance himself from the community.”

A view of the large house in 1983 that Fernando Valenzuela built for his family in Etchohuaquila, a small town within the municipality of Navojoa in the state of Sonora, Mexico.

(Bob Chamberlin / Los Angeles Tim)

La Casa looms above a mostly flat landscape dotted with mesquite bushes. A Los Angeles Times account from 1983 referred to the house, tongue in cheek, as “the adobe equivalent of Lincoln’s log cabin,” noting how Fernando fanatics flocked to the site, even breaching the wire perimeter to peer inside the windows.

“Fernando’s house, like Fernando, is public property,” the article said. “He is everybody’s son, and this is everybody’s house.”

Several surviving siblings, in-laws and others still reside at La Casa. They mostly avoided the media invasion that ensued upon word of Valenzuela’s death. But the family invited relatives, neighbors and others to an open-air memorial Mass Thursday evening in the patio behind the home.

A flower-bedecked, near life-sized photograph of Valenzuela hurling from the mound in Dodger blue-and white stood to the right of the makeshift altar.

“Fernando Valenzuela was always a humble person who, through perseverance and ability, managed to overcome difficult circumstances and become a great star of sports,” said Father Baudelio Magallanez García. “We are here in the house that he built, a blessing for his family. And he is an inspiration for many young people — who, hopefully, will follow this path and not evil ones.”

His relatives, as is their custom, had little to say. Still lingering, for the family and others, is an enduring mystery: How did Fernando Valenzuela make it all the way to the top from that bumpy patch of sun-baked earth?

“I don’t know,” said his brother Gerardo, shaking his head. “All of the brothers in the family played baseball. All of us. But, for some reason, only Fernando could reach such heights.”

Special correspondent Miguel Valenzuela (no relation to Fernando) in Etchohuaquila and Cecilia Sánchez Vidal in Mexico City contributed.