LONDON — Contemporary artist Mike Kelley’s first major U.K. exhibition has landed at the Tate Modern with a sea of his work, including downtrodden, tangled-up toys; crystalline recreations of Superman’s hometown, Kandor; and a mythologized “Banana Man.”

The retrospective, titled “Mike Kelley: Ghost and Spirit,” will run until March 9 and borrows its name from an unpublished screenplay written by the artist.

“The script says, ‘A ghost is someone who disappears, an empty concept. A spirit is a memory. I’m a ghost, I have disappeared. I’ve disappeared, but survive in others,’” said Beatriz Garcia-Velasco, the show’s assistant curator in an interview.

Mike Kelley’s “Banana Man” costume is also on display.

Courtesy of the Tate Modern

“There’s something a bit self-deprecating about saying, ‘I have disappeared,’ but his obsession with questioning the role and identity of the artist in his work is something that echoes throughout the exhibition,” she added.

Originally scheduled to be shown pre-COVID-19, the pandemic’s sudden onset pushed the show back until now.

Laid out in chronological order, the exhibition traces the artist’s career from his days as a California Institute of the Arts student to his final work “Extracurricular Activity Projective Reconstructions.”

Kelley’s high-octane work, jam-packed with childhood memories, low-brow pop culture references and found objects, feels particularly timely for a world in flux.

While not necessarily imbued with optimism — Garcia-Velasco describes the show using words such as “uncanny,” “eerie,” “eviscerated corpse,” “trauma,” and “alienation” — there’s a sense of naiveté to Kelley’s work. Or a longing for one, at least.

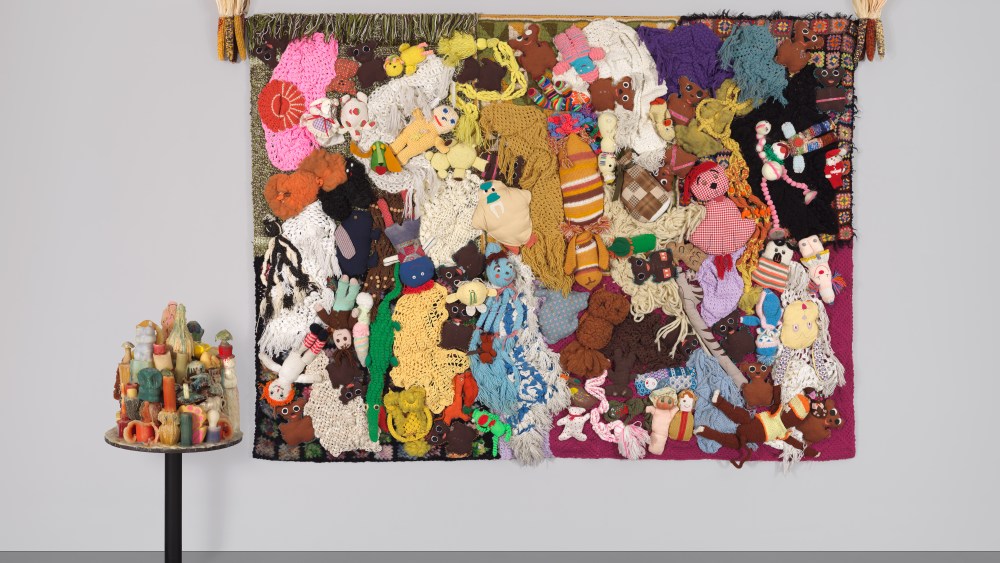

Detail of Kelley’s “Ahh…Youth!” from 1991.

Courtesy of the Tate Modern

Taking center stage at the exhibition is Kelley’s “Half a Man,” work — a breakout series composed of felt banners, refinished furniture, “garbage” drawings and black-and-white paintings capturing the fleeting chastity of childhood, but it was his amalgamation of soiled stuffed animals that captured the public’s imagination. Whether stitched together then strung up from the ceiling or wall, or embroidered onto a baby blanket, audiences left reflecting on themes of child abuse.

“I said, ‘well, that’s really interesting. I have to go with that. I have to make all my work about my abuse – and not only that, but about everybody’s abuse. Like, that this is our shared culture.’ This is the presumption, that all motivation is based on some kind of repressed trauma,” Kelley explained in reference to the public’s perception during a 2005 PBS documentary series.

The beauty in Kelley’s work lies in the surreal abstraction of his dark reality — his ability to break down the hardest experiences into bite-sized pieces.

The artist was born in 1954 to a working class background and grew up in Michigan. His work often drew on his childhood trauma and led him to become one of the U.S.’s most acclaimed multimedia artists. He died in Los Angeles in 2012.