Todd Lerew is curious. He likes lists. And he doesn’t like doing things halfway.

This is why he collects pictorial maps, why he has visited 248 public libraries in Los Angeles County and 401 of the 483 municipalities in California. It’s why he recently joined the Fraternal Order of Eagles, the Elks, Moose International, Oddfellows and about 50 other clubs — so many that he had to get a separate wallet for membership cards.

This may seem like a lot of projects for one 37-year-old, who calls them “acts of compulsive nerdiness.” But those interests pale next to Lerew’s passion for unsung museums and collections.

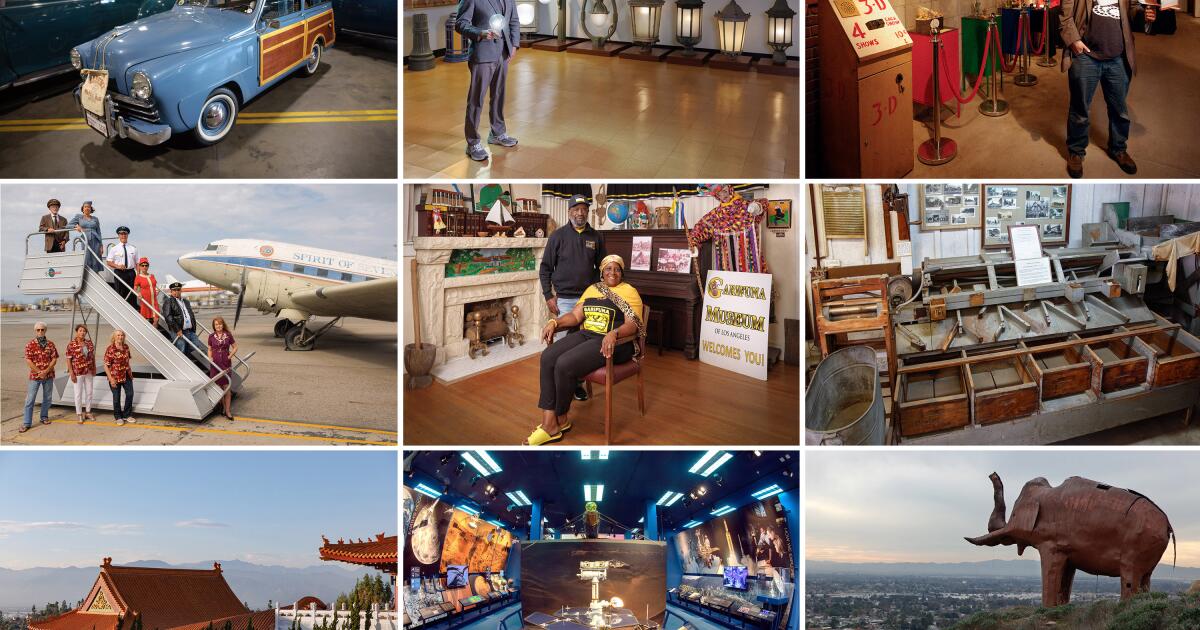

That’s the subject of his new book, “Also on View: Unique and Unexpected Museums of Greater Los Angeles,” published this week by Angel City Press at Los Angeles Public Library.

The volume, an illustrated exploration of 64 museums whose names you are unlikely to know, draws on a decade of research and stands as a challenge to all Angelenos who think they have a handle on the local cultural landscape.

These are ventures — often one-person crusades — that celebrate fast food, Finnish folk art, Skid Row, skateboarding, vertebrate zoology and more. Yes, the Museum of Jurassic Technology in Culver City is here. Yes, the U.S. Navy Seabee Museum in Port Hueneme and the Cucamonga Service Station Museum too.

The Museum of the Republic of Vietnam in Westminster? The Parsonage of Aimee Semple McPherson in Echo Park? The Historical Glass Museum in Redlands? Lerew and photographer Ryan Schude visited them all.

“There’s nothing you can say about museums that’s true of all of them,” Lerew said one recent morning. “And you can find them everywhere you look.”

Indeed, he spoke near the Long Beach waterfront, surrounded by unremarkable skyscrapers and zero foot traffic. But a block away stands the Outer Limits Tattoo and Museum, opened in 1927.

This was first of two stops where Lerew planned to deliver copies of the new book to people who are in it.

The oldest operating tattoo shop in the U.S.

Inside Outer Limits, founder and tattoo artist Kari Barba, 64, eagerly unwrapped a copy of the book. Barba, a celebrated tattoo artist and industry pioneer who runs a second tattoo location in Costa Mesa, said she bought the Long Beach space 20 years ago because “I was really hurt by the idea that the history of the building would be lost.”

Barba led Lerew and a visitor through the restored rooms; the tables and modern tools now in use; the antique tools; the stencils of anchors, hearts and dragons; the old photos of inked sailors at the long-gone Pike amusement park; a hand-painted window that workers found hidden in a wall; and, in one corner, a mysterious covered vat.

“You’ve got to see the vaseline before we go,” Lerew said.

So Barba and Lerew stepped to the vat and uncovered it, revealing a glutinous stew of rags and vaseline, once integral to the tattoo process; the stew’s age and precise contents are uncertain.

“I don’t know what’s in there. I’m not reaching in to find out,” Barba said.

“Distinctive smell, also,” said Lerew, leaning to sniff.

What shapes a compulsive collector?

Lerew, who lives with his wife in Lincoln Heights, grew up in rural South Dakota. His family made regular trips to roadside attractions such as the faux cowboy town at Buffalo Ridge and the Corn Palace in Mitchell, where something about “the curious, the unique and the obscure” got under Lerew’s skin.

After graduating from Hampshire College in Massachusetts, he came west in 2009 and went to grad school at CalArts, focusing on experimental music composition. But his attention strayed, a trait that became a professional asset when the Library Foundation of Los Angeles hired Lerew as program manager in 2015.

In his off hours, he’d check out other libraries and museums — often six or seven in a day, all logged on a spreadsheet. To find them all, he’d check Boris Stanic’s guidebook, “Museum Companion to Los Angeles,” as well as scanning the web and talking to friends and strangers.

In 2016, after months of hearing from Lerew about his weekend explorations of obscure collections and archives around Southern California, the foundation’s president, Ken Brecher, assigned Lerew to curate an exhibition on local collectors that became “21 Collections: Every Object Has a Story.”

“I’ve always collected experiences of one kind or another,” Lerew said. “I was just exploring because I had a private interest and obsession in finding new and unique places and people. It kind of got formalized when i started working on that exhibition.”

What makes a museum?

Lerew said he’s eager to see just about any place that calls itself a museum, whether or not it has nonprofit status or academic credentials or a permanent home. He’s also drawn to spaces that might not call themselves museums but often behave like them, including park visitor centers or college art galleries.

When it comes to selfie-driven exercises like the nationwide Museum of Ice Cream chain (which had an L.A. pop-up location in 2017), he’s not so interested.

And in every museum, he considers the source carefully. At most historical museums in the U.S., he said, “It’s the white people’s history of that area,” omitting much and perhaps whitewashing much else.

“You just have to be aware, when you’re going to these places, of who is telling the story,” he said. “There are more stories out there, always.”

By the time his “Collections” show went up in the Central Library in 2018, Lerew had scouted more than 600 locations, enlisting collections that included paper airplanes (from the Getty), typewriters (from Tom Hanks), candy wrappers and birds’ nests. From that project came a self-published book, an Instagram campaign (@museumaday) and now the new volume, coffee table-ready.

By hand, she re-creates key moments in Black history

“Oh, big pictures!” Karen Collins said when Lerew arrived at her home in Compton and handed her the book. “I don’t know why, but I was picturing something small.”

Small, after all, is Collins’ specialty. Around her living room, miniature dioramas of crucial moments in Black American history took up much of the horizontal space. A “Black Lives Matter” triptych, made for the Central Library’s “21 Collections” exhibition, sat above the fireplace.

Collins, 73, a retired preschool teacher, creates the dioramas, making and arranging miniatures within shadow boxes made by her husband, Eddie Lewis. She started about 30 years ago, after her son was sent to prison as a 12th-grader and she felt “ready to die.”

She pushed grief back by resolving to portray key figures and moments in Black history, to inspire and educate grade-school children, “and let them know, you can get over anything. … The art saved my life.”

There have been dozens of dioramas since then, depicting scenes from the Middle Passage to Harriet Tubman, Malcolm X, Martin Luther King Jr., Thurgood Marshall, Colin Powell, the Obama inauguration, Compton Cowboys and Kendrick Lamar.

For years, Collins and her husband brought shadow boxes — their mobile museum — to schools and community events. Lerew spotted her work on display in Leimert Park.

Lerew: “How many of these have you made over the years?”

Collins: “A lot. Because I give them away.”

Beyond Lerew’s Central Library exhibition and book, Collins has been commissioned by the Autry Museum (where several dioramas are part of the permanent exhibition “Imagined Wests”), profiled by national media outlets and chosen to provide a Google doodle for the 60th anniversary of the Greensboro, N.C., civil rights sit-ins. Her son, still incarcerated, “is proud of me,” she said.

Now she’s working on a coloring book and hoping to find “a stable place for this museum to be … for our children to see their worth,” she told Lerew.

“It’s a really tricky thing,” Lerew said later, “when it’s one person’s passion project. … I can’t say what might happen for Karen’s collection. I have hopes. Time will tell.”

Is Lerew done with little museums now? Absolutely not.

Beyond those in the book, he’s put another 700-plus large and small Southern California museums onto an everymuseum.la website, now live.

Then there’s the other list on his phone, where he has keyed in all the unseen museums he wants to visit. Worldwide. There are 3,231 of them.